This week we were given free reign to explore all of the topics for the next five weeks which should lead to a Digital Humanities Advancements grant proposal draft and some sort of prototype. Like my colleague Teresa Goforth, I wanted to jump ahead to the mapping section. But I decided that I should get some of the basics out of the way first, since most of this is new to me. Therefore, I spent the week looking at platforms to organize archival data.

As you may notice, I did not post on my usual day: Tuesdays before we have class. That is because I spent way too much time fiddling about with platforms. I learn best by screwing things up (the Beetle in the picture below is a great example of a car I completely destroyed as a young whipper-snapper) so I spent the week trying to break things. After hours of dead-ends, Google searches, and learning a bunch of new acronyms, I can say that nothing is broken and I became quite acquainted with Omeka and Scalar.

What I learned most this week as I test-drove out these platforms, was that my archival skills are completely horrendous. This comes as no surprise to me. I tend to think only about the now when working on projects. I always lose stuff. I can’t tell you how many 13mm wrenches I have owned over the last twenty years. No matter how many pegboards and toolboxes I have in the garage and basement, there seems to always be a void where I thought I put that wrench. My organization skills are ridiculous. I imagine there are many whose heart rate would quicken when they look at my Gmail inbox number (11,921). These same habits cross over into the historical data I accumulated over the last decade. Metadata? Oh. I’ll deal with that after I have this paper finished for the conference tomorrow. Yeah, right.

To test-drive new platforms I attempted to transfer the information from my Listening to the Past page I started on the WordPress site and also started an exhibit of Progressive Era marketplaces in Grand Rapids. I wanted to see how different types of files work. I can say I did not succeed at either yet, but I did learn a lot on how each platform operates (For example, the FTP client in Omeka is built into our domains page which would have been good to know while I was square-hole pegging with a client on my PC). More important, I learned that I need to be better about provenance and rights.

It is quite humbling to stare down empty metadata fields. “Where the hell did this come from?” came up quite often. Sometimes this was followed by, “Oh, I have two other copies with some information in the filename.” This compounded when thinking about recordings I have. Some are interviews. Could the people still be alive? Should I track them down before posting this? Their descendants? One recording is from the defunct CCCP Soviet recording company. Are there copyright issues with that? I looked up what I could, and the legal ramifications were clear as mud on it. Luckily, my proposed project for this course is tentatively a mapping archive which shows food environments of Michigan cities during the Progressive Era.. It is highly doubtful that ethical issues will arise. Still, my undergraduate background in anthropology and interest in Cultural Resource Management always has me thinking about ownership of local knowledge.

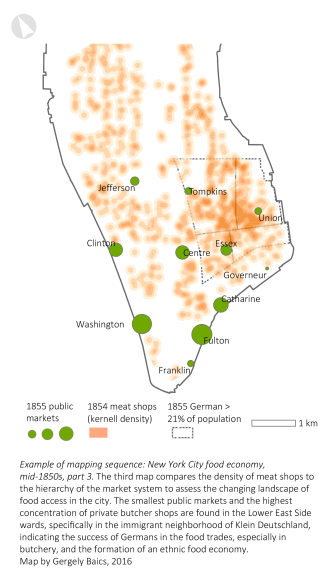

This is a map created by Gergely Baics of Barnard College, Columbia University on food access in 19th Century New York City. My goal is to develop this idea for smaller cities around the US. Check out his work here. For the names of the team responsible for all this work see the Appendix of Feeding Gotham.

The work done to create content management systems (CMSs) like Mukurtu is fascinating. Kimberly Christen’s article on the creation of a Traditional Knowledge Labels for users from indigenous communities to claim intellectual rights to archival sources by providing access to metadata gave a glimpse into the issues of promoting cultural knowledge while retaining control for those whose heritage is being shared. She brings up an interesting point which I had never thought about. One usually thinks of Public Domain sources as a feel-good place where some corporate entity is not lording over information. Yet, as Christen points out, much indigenous cultural knowledge has been put into the public domain without the consent of the creators, perpetuating the colonial domination of archives. It is important for all historians to think about how their archival data was created and if there are lingering inequities of power.

I plan to fiddle around with these sites more, but will more than likely abandon the projects I started to focus on the prototype for this course. Next week I will be diving into text analysis. I have no idea what this will entail. I’ll let you know next Saturday what I find out as I rip apart some more things.