So, it has been a long time since I wrote anything. Things got a bit crazy last semester. No need to get into my own issues here, though. You never know what life may throw at you, but as our sage professor in my current methods seminar, Dr. Delia Fernandez-Jones, reminded us this week, not attaining your goals does not make you a failure. It usually just means you either had unrealistic goals, too many of them, or other stuff simply got in the way. Gotta dust yourself off and get back in the saddle.

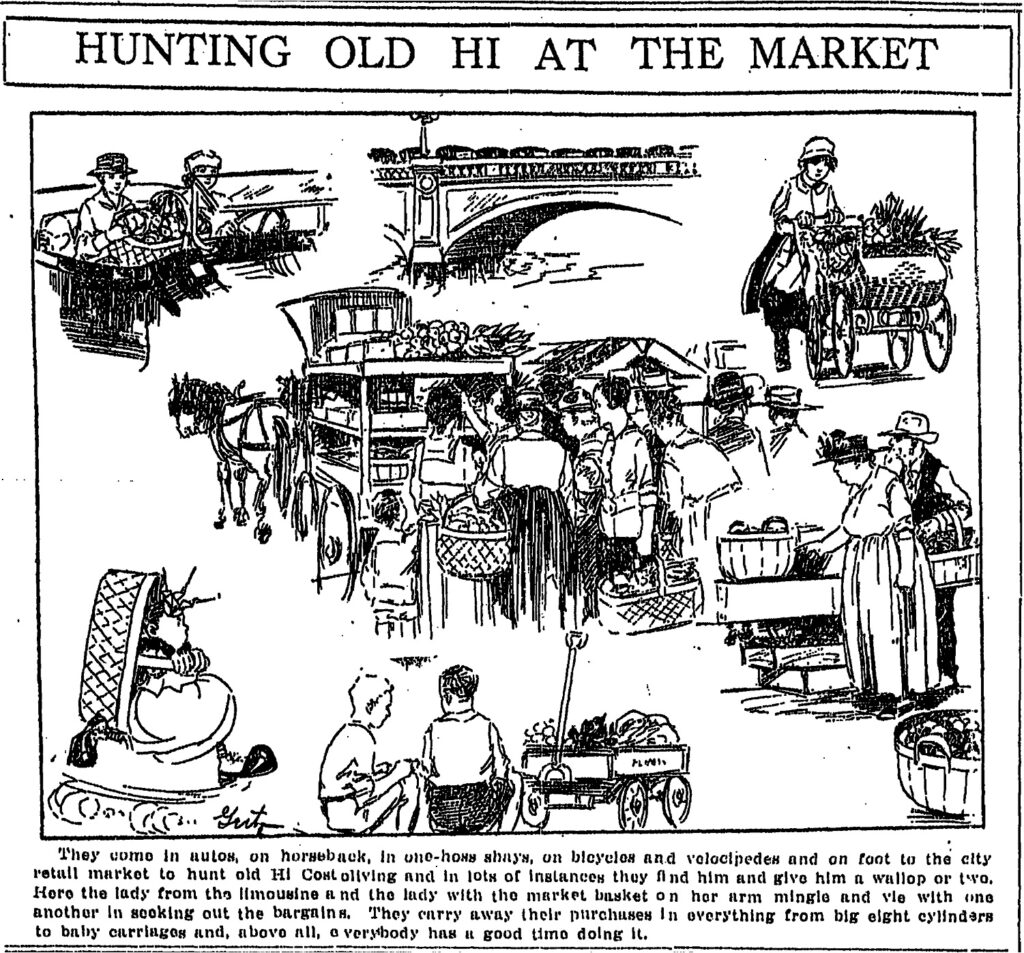

My previous blogs were more of a practice in getting comfortable writing something that would be published online each week. From here on out I will be more focused. Specifically, these blog posts will help me work out the nuts and bolts of my dissertation. Currently, my topic is local politics around food distribution and consumption in western Michigan during what is known in traditional US periodization as the Progressive Era, roughly from the turn of the 20th century to the end of the 1920s. More specifically, I am interested in what we would call “Alternative Food Systems” (AFSs) in today’s academic parlance, i.e. farmers markets, public gardening programs, etc. Whether I hang my work on this periodization is still not clear. Two semesters ago I took a course with Dr. Pero Dagbovie and he challenged us to think about what “turning points” are important for our own historical narratives and the subjects we study. For example, the “Progressive Era” is considered “the Nadir” in most African American historiography. Nevertheless, for now, I will be using Progressive Era as a short-hand for the time period I am looking into. Maybe a later blog post will tackle periodization.

Since this is my last semester for taking seminar courses, I will be pulling together strands I traversed over the last two years, bundling theory and methods honed during this period with nearly two decades of food systems studies. My starting point is a master’s thesis I wrote in 2011 on the origins of retail farmers markets in Grand Rapids, Michigan. This research led to the discovery of the work by citizens, most notably white middle-class clubwomen, and their involvement with not only promoting public food marketing, but also growing food through public gardening programs. You can check it out here, and also a book chapter here. The most obvious weakness in these works is a lack of relevance. It sure seemed important to me to craft my narrative, but I was studying a marketplace which I managed for three years~and was down the street from my house!

I do make some claims and back them with evidence, however. For example, I tie the markets to current trends in privatization/gentrification of public marketplaces, claiming that markets should be a public service. And I do claim that most historical antecedents in the alternative food systems literature oversimplify the history of farmers markets, notably ignoring the increasing number of publicly-supported markets in mid-sized cities toward the end of the teens and into the 1920s. Yet, as one of our astute colleagues in my current methods seminar, Raymundo Lopez, shared from their experience working on research projects abroad: So What?

This Warrants a Closer Look

Does it really matter if heavyweights in food systems work like the late Thomas Lyson explicitly claimed that “the number of farmers market in the United States began to decline in the 1920s with the advent of the modern supermarket,” when the data shows this as patently false?1 Even if it was true on a national level (which it is not), in Michigan, at least twenty markets were started through the state in the 1920s. This historical framing has made its way into the historiography (a recent article in Sustainability is an exception).2 But why does it matter to get this right? What does it tell us that markets increased during this period? Why does it warrant further research? As a colleague told me during my defense of my master’s thesis, simply showing others are wrong is a strawman argument. Why does it matter they were wrong?

I know that my research does not currently have the relevance I would like. I tend to get one of two reactions when I tell people what I study. Some are super interested because they have personal connections to my subject such as living in Grand Rapids or are crazy foodie people. Mostly, though, they just stare at me blankly with a look of “Yeah, so what?”. But what I study has to be relevant, I mean they accepted me into a doctoral program, right? Everyone eats. That means everyone must care about food. Unfortunately, we tend to get self-important when we immerse ourselves in our research.

Using Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams seminal work The Craft of Research as a guide, I want to find an argument that matters, starting with a visualization of their outline of an argument.3

A good argument begins with a claim, which states an idea that will be proven true or false in a study. Claims rely upon reasons, which are backed by evidence. In reality, a study could make multiple claims each justified by multiple reasons based on a bevy of evidence. This is very clear and easy to understand. For example, I could claim that the city of Grand Rapids opened its first retail farmers markets in 1917 because clubwomen demanded such spaces from the city government. This reason is based on newspaper articles, city council/commission proceedings, and publications/meeting minutes of clubwomen. While this is technically an argument, there are crucial elements missing which make it a good argument. And, my argument should be a reason for a larger claim which has broader traction. As Booth et al write, “Serious arguments are complex constructions.”4 So, let’s complicate things.

The more I look back at my previous research and writing a few claims come to the fore. The broader claim I want to make is that Michigan farmers markets were part of an Alternative Food System that promoted food justice during the Progressive Era. And to bring this out even further, I could argue that just and sustainable alternatives to the mainstream, industrialized food system can find historical their origin (and similar criticisms of paternalism) in grassroots political, or more aptly civic, activism of the Progressive Era. There are issues with such a claim. First and foremost, one could realistically argue I am being anachronistic. The alternative food movement is traditionally historicized as an extension of 1960s social revolutions and prior arrangements such as farmers markets and urban agriculture tend to be framed as remnants of a nostalgic past or emergency measures in time of economic shock. Further, the Progressive Era is presented in the historiography as a time of increased mass consumption of food where modern technology and standardized diets were embraced, not pushed back against through local food campaigns and urban agriculture. Booth et al write that researchers should anticipate such arguments and “thicken” their arguments so they are ready to respond without bruising their ethos. In other words, not being the ass no one want to include in the conversation. I do have some evidence for the acknowledgement and responses against potential criticisms which I plan to cover later.

Yet, acknowledgment of possible counters is not the final piece. Booth et al add one more element, which as they admit, is the most difficult concept to wrap one’s head around, and what I want to bring up here and continue next week. Between the claim and the reason is what they call the warrant. A warrant gives the “because of” teeth. For example, the unprecedented increase of municipal and county operated retail marketplaces where farmers sold directly to consumers in Michigan between 1910 and 1930 is attributed, at least in part, to the work of prominent white women leveraging local politics. This is a reason for claiming that alternative food systems were being established through civic work which promoted food justice. Yet, what makes these food arrangements “alternative” and why is this an issue of food justice? In other words, what warrants this reason? Well, considering the latter, previous research has shown that chain grocers, which made food more reasonable during the high cost of living of this era, were not evenly distributed in cities. For the former, chain grocers were becoming the “norm” for many consumers, however, and they were an alternative to the neighborhood independent grocer which dominated throughout the late 19th century and into the 20th. For these reasons, the establishment of these markets mark an alternative to the established and emerging food retailing in areas which were not being served by chain grocers. I understand this may not be a watertight warrant and may not explain the idea of warrant super clearly, but it is a beginning. I need to further elaborate on the idea of food justice if I am to continue thinking about the relevancy of my argument, and will pick up next week there.

I want to leave with a quote from Lynn Hunt. My goal is to find an argument which has relevance for those currently working to make food access equitable. She writes: “Wisdom can be found in learning about how people in the past confronted their challenges.”5 I hope that by digging deeper into what I scratched earlier, I can discover some of that wisdom, not just from those obvious in the archive, but the actors who worked for change in their own neighborhood. So, come back next week when I continue looking for and argument and relevance. I also will begin looking at some of my evidence which may induce a new argument.

- Lyson, Thomas A. Civic Agriculture: Reconnecting Farm, Food, and Community. UPNE, 2012. p.92

- Edmonds, Amanda Maria, and Gerrit J. Carsjens. “Markets in Municipal Code: The Case of Michigan Cities.” Sustainability 13, no. 8 (January 2021): 4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084263.

- Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams. The Craft of Research, Third Edition. University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Ibid. p. 117

- Hunt, Lynn. History: Why It Matters. Newark, UNITED KINGDOM: Polity Press, 2018. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/aquinasmi-ebooks/detail.action?docID=5376186.